Joe Clifford was my

2014 Bouchercon revelation. Following up with his heavily autobiographical

novel,

Junkie

Love, put the hook in

me deep and earned him an instant spot in my reading rotation. His latest book,

Lamentation, dropped last fall and showed so well he

already has a contract for its successor.

Joe has the

engaging and endearing quality of being able to talk about his strengths and

weaknesses without exaggerating the former or making excuses for the latter.

His blog,

Candy and Cigarettes, has become a must read for me, for those

qualities, and the quality of writing.

The timing worked

out and I was lucky enough to catch Joe for Twenty Questions on his way to AWP;

he was gracious enough to turn the interview around the same day. Let’s get to

it.

One Bite at a Time: Tell us about Lamentation.

Joe Clifford: It’s a mystery, revolving around two

brothers and a missing hard drive, which may or may not contain secrets

involving a prominent, small-town family. I mean, that’s the elevator pitch.

OBAAT: Where did you get this idea, and what made it worth developing for

you? (Notice I didn’t ask “Where do you get your ideas?” I was careful to ask

where you got this idea.)

JC: Lamentation, interestingly

enough, began as my thesis for grad school. I mean, sort of. The end result is

so radically different from the inception that I’m not sure it’s even fair to

call it the same book. The final version retained exactly one line from the

original: “A talking chicken named Buck Buck.” The gist of the story I wanted

to tell, though, remained the same: two brothers, one a drug addict, one the

straight man. But that is such a loose definition. More a guideline than a plot

point. Anyway, so back to your original question. They say that the first novel

you write is your autobiography. Junkie

Love is my autobiography. Lamentation

is actually the fifth book I’ve written, but it retains many

autobiographical elements. The town in the novel is called Ashton, which is

fictional and set Northern New Hampshire, but the geography I use is based very

much on my real hometown of Berlin, CT. And at its heart it is still the story

of brothers and all the weight that comes with that label.

OBAAT: How long did it take to write Lamentation,

start to finish?

JC: Not counting the aborted grad school attempt? About six months. Once I

learned how to write a novel, all my books take about the same amount of time: three

to draft, one-and-a-half to sit on (as Stephen King tells us), and another

month and a half to rewrite.

OBAAT: Where did Jay Porter come from? In what ways is he like, and unlike,

you?

JC: I think every character—certainly every hero—contains bits of the

author. Maybe I shouldn’t speak for everyone. All my heroes contain parts of me. But Jay is also very much based on

my half-brother (also named Jay). I find it helps if I can picture someone as I

write him/her. When I was writing the character, I’d envision my half brother,

who’s a sweetheart of a guy, but someone who never can … quite … get … it …

going. You know the type. Save $900, and the transmission goes. Jay is also a

stand-in for the everyman chasing the illusion of the American Dream.

OBAAT: In what time and place is Lamentation

set? How important is the setting to the book as a whole?

JC: Around 2010. Ballpark. As I mentioned, the setting, well, the fictional

setting, is Northern New Hampshire, by the Canadian border, and it’s the dead

of winter. I know there is an edict that talks about how authors should use

setting. It might’ve been Elmore Leonard who said never describe the weather.

And rules like that are good as general rules. You don’t want to be lazy. But

in this story, I felt the weather very germane to what I was trying to do. I’ve

lived in three distinct regions in my life: San Francisco, New England, South

Florida. And in each case, the weather has played a huge part in my life. So I

have always been drawn to that element, so to speak. Here, though, in Lamentation, setting is even more

integral to the story I am trying to tell. Which is one of the reasons I

couldn’t use my hometown in Connecticut, which is south and not quite as brutal

in the winter. I needed that hard, cold, infertile landscape (of Northern New

Hampshire) to mirror the scrounging and fruitless digging of these characters.

OBAAT: How did Lamentation come to

be published?

JC: Lamentation is my first

effort with a house this big (Oceaview Publishing put it out. They’ve also

picked up the sequel, December Boys).

The short version is my agent sold it! The longer version is I had to first get

that agent, the wonderful Elizabeth Kracht with Kimberley Cameron and Associates.

Which was the harder of the two really, honestly. Agents are so inundated with

requests for representation that you need to find unique—yet organic—ways to

catch their attention. In this case, Liz declined (regretfully) to rep Junkie Love (a book she saw as too

gritty for commercial appeal). When that book sold and started to do well,

albeit on a smaller, cultish scale—and, more importantly, Liz saw (through

Facebook, of all places!) how hard I work at promoting—I think I was on her

radar and that she wanted to work with me. Which flipped the dynamic a bit. Which

touches on another HUGE point: authors these days have to be willing to do their own marketing. I know a lot of

writers who think their only job is to write the damn thing. Not true. Even the

big houses expect you to do a lot of the legwork to help guarantee a book’s

success.

OBAAT: What kinds of stories do you like to read? Who are your favorite

authors, in or out of that area?

JC: I always make the same joke, but I named one son Holden and the other

Jack(son) Kerouac. That answers that.

OBAAT: What made you decide to be an author?

JC: Brain damage from years of drug abuse? I don’t know. I think I bought

into that romanticized notion of the author. The great man of letters. Which is

bullshit, really. It’s work, like anything else. You want to get good at it,

you have to dedicate your life to it. On the one hand I say if I had known how

much work that was, and for how little pay off, I would’ve picked another

career. But that’s bullshit, too. I, like other authors, entered this field

because it’s who I am. Also, I was too old for

rock and roll.

OBAAT: How do you think your life experiences have prepared you for writing

crime fiction?

JC: I was a criminal, so that helped.

OBAAT: What do you like best about being a writer?

JC: Not having to wear pants to work.

OBAAT: Who are your greatest influences? (Not necessarily writers. Filmmakers,

other artists, whoever you think has had a major impact on your writing.)

JC: Man, this is going to sound cheesy as fuck. Especially from a crime

writer, but, man, as I get older, my mother and the kind of woman she was

stands out more and more. She died in 2004, about two years after I got off

heroin. So she never got to see this, the successful parts, my sons. I try to

be the man she always believed I could be. Sentiment aside—Rocky. No shit.

Rocky Balboa, while a fictional creation, played a huge role. He is such an

iconic character, represents such an indefatigable American ideal, and one that

touches on what I, as a person, do well. In the end, my biggest skill is I can

bang my head against a wall longer that you. It’s a useless superpower often

times, but it has saved my ass more than once. (Kicking heroin comes to mind.)

Others? Philip Marlowe, Holden Caulfield, and Batman.

OBAAT: Do you outline or fly by the seat of you pants? Do you even wear pants

when you write?

JC: Ha! No. I don’t. Y’know, each book has been different. Junkie Love took about ten years to

write, but that’s not a fair assessment. I didn’t know how to write a book when

I started, so I had a lot of scenes. Lamentation,

too, began before I had craft down. I owe a great deal to Lynne Barrett, my

thesis advisor at Florida International University, who got it through my thick

skull that two dudes sitting around a café talking about girls isn’t a story;

it’s self-indulgent, navel gazing, pap. But the quick answer is no, I don’t

outline. I have for one novel (Skunk

Train). Love the book. But in the end I think that outline added time, not

saved it. Made the process feel too much like work. (Like most writers, I’m

sure, I am lazy. Or rather, I don’t like to feel

like I am working. I probably “work” sixty-plus hours a week. But it’s for

me. On my terms. Big difference.)

OBAAT: Give us an idea of your process. Do you edit as you go? Throw anything

into a first draft knowing the hard work is in the revisions? Something in

between?

JC: This and that. I generally stagger. By that I mean, I get a bunch out,

say, 50 pages. Then I go back and reread, tighten, get the voice in my head,

then write another 50, and do the same thing.

OBAAT: Do you listen to music when you write? Do you have a theme song for

this book? What music did you go back to over and over as you wrote it, or as

you write, in general?

JC: I do! Each book gets a soundtrack. This one was heavy on Springsteen.

For the sequel, I steal the title, December

Boys, from the Two Cow Garage song, “Jackson, Don’t Worry.”

OBAAT: As a writer, what’s your favorite time management tip?

JC: Twofold. Be consistent. And stay off the Internet. The brain is a

muscle, man; it needs to be stretched. Even if you are writing/typing “I don’t

know what to write” over and over, eventually something clicks. I don’t believe

in writers’ block. Not that we all don’t

get sopped up, from time to time…

OBAAT: If you could give a novice writer a single piece of advice, what would

it be?

JC: Quit and get an MBA. If that doesn’t dissuade, don’t give up. This shit

is a marathon, not a sprint. Just because that is a cliché doesn’t make it any

less true.

OBAAT: Generally speaking the components of a novel are story/plot,

character, setting, narrative, and tone. How would you rank these in order of

their importance in your own writing, and can you add a few sentences to tell

us more about how you approach each and why you rank them as you do?

JC: Plot and character are 1 and 1.2. The others don’t exist without it.

Plot is the most important thing because that

is what is fucking happening. Coming from an MFA program, I experienced a

great deal of a resistance to plot. I mean, that’s the world of literary

fiction. Like plot is a dirty word. Fortunately for me, I went to FIU, which,

unlike most MFAs, embrace genre (which relies heavily on plot). As readers we

like to be swept up by a great narrative. As writers, we tend to resist plot.

Lynne used to say this is because writers are so internal; it’s our go-to

position, our default. But you can’t have a best seller without plot. And I

want a bestseller.

OBAAT: If you could have written any book of the past hundred years, what

would it be, and what is it about that book you admire most?

JC: Catcher in the Rye. It’s a

perfect book. Which is a little funny since the plot in that one is a little

light. But stuff does happen. Holden’s

trip home after getting kicked out of prep school is fraught with adventure and

peril. Shit happens. It’s just that his voice is so strong, and what he represents as the disillusioned teen so

compelling, that we sometimes overlook the storyline re: Pency and Jane and

Maurice, etc.

OBAAT: Favorite activity when you’re not reading or writing.

JC: Fantasy football and weight lifting. (I’m a closet jock.)

OBAAT: What are you working on now?

JC: The sequel to Lamentation, December Boys, which has already been

sold to Oceanview, and is slated for 2016 release.

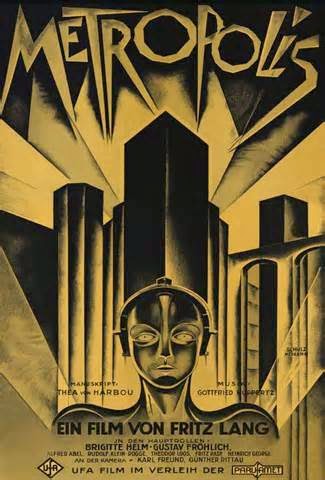

Appaloosa (2008).

Robert B. Parker turned to Westerns when the Spenser series started to run out

of gas. (Not that he stopped writing Spensers.) Appaloosa was the first, and Ed Harris apparently fell in love with

it, as he produced, directed, starred in, and co-wrote the screenplay. A solid

Western of the male-bonding genre, as Harris’s Virgil Cole roams the West with

Everett Hitch (Viggo Mortensen), hiring on as the law for towns that need it.

No one wrote man-to-man laconic dialog better than Parker, and Harris wisely

kept a great deal of it. The only weak point is the casting of Renee Zellweger

as Allie French, the stray woman in town, who hooks up with Cole, unless

someone more promising is available. (And breathing.) That character is the

weak point of the book, and Zellweger does the part no favors. Diane Lane was

originally cast, but dropped out in pre-production (per IMDB); I could have

believed Cole doing uncharacteristic things for Diane Lane.

Appaloosa (2008).

Robert B. Parker turned to Westerns when the Spenser series started to run out

of gas. (Not that he stopped writing Spensers.) Appaloosa was the first, and Ed Harris apparently fell in love with

it, as he produced, directed, starred in, and co-wrote the screenplay. A solid

Western of the male-bonding genre, as Harris’s Virgil Cole roams the West with

Everett Hitch (Viggo Mortensen), hiring on as the law for towns that need it.

No one wrote man-to-man laconic dialog better than Parker, and Harris wisely

kept a great deal of it. The only weak point is the casting of Renee Zellweger

as Allie French, the stray woman in town, who hooks up with Cole, unless

someone more promising is available. (And breathing.) That character is the

weak point of the book, and Zellweger does the part no favors. Diane Lane was

originally cast, but dropped out in pre-production (per IMDB); I could have

believed Cole doing uncharacteristic things for Diane Lane.